Don't fall into a midlife crisis - it's an opportunity

Sep 02, 2021

I was delighted to give my thoughts for a feature in the Irish Independent on the female midlife crisis.... although I argue that it is no such thing. Challenging yes, but an opportunity to start living life on your terms. 💪.

For those who don't subscribe.. here is the copy:

‘It’s a fundamental change to who you are’: How to survive the female mid-life crisis

Mid-life brings hormonal changes, family challenges, career dilemmas and existential angst. But it can also be a time of rebirth and new opportunities

Katie Byrne, September 2nd, 2021

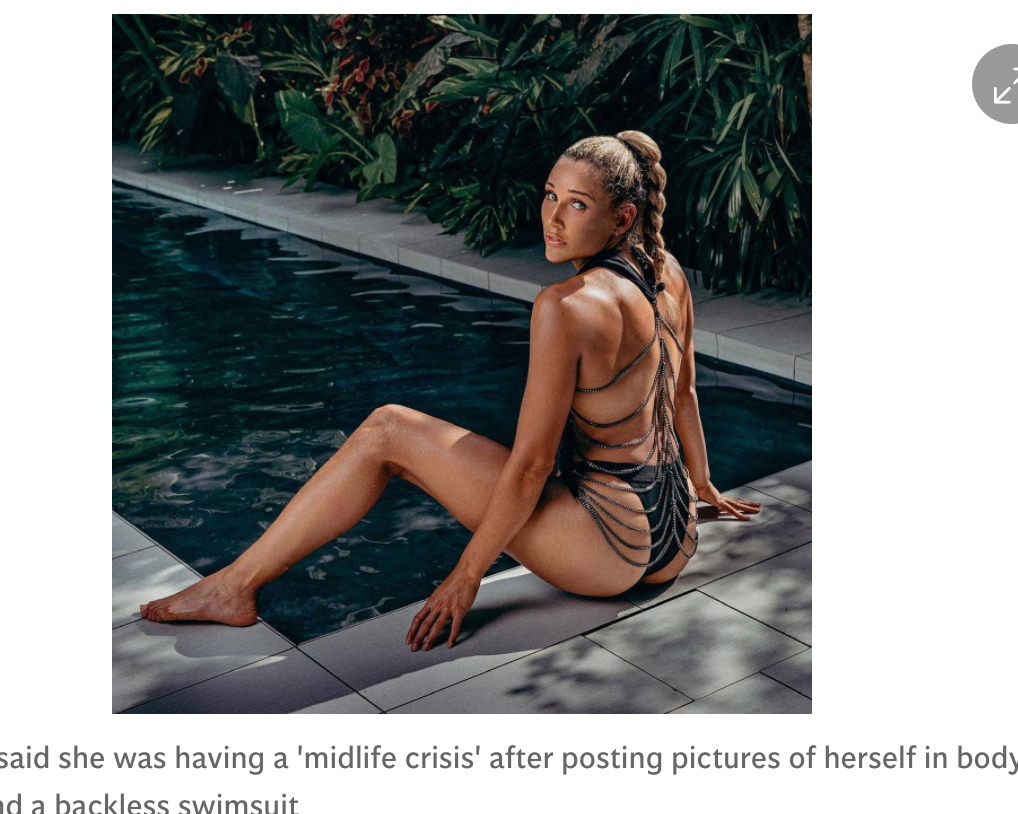

Three-time Olympian Lolo Jones recently took to Instagram to post a series of stylised swimwear shots.

Wearing a backless swimsuit decorated with body jewellery and a come-hither gaze, she told her followers that she was publishing the “thirst trap” photos because it was her last year in her 30s. “I’m having a midlife crisis,” she wrote in the caption. “Next year, I’ll be wearing mom jeans and driving a mini van.”

The photos were well received by Lolo’s online followers, but they also sparked some questions. Does a woman have to apologise for looking sexy after the age of 35? Can a midlife crisis really arrive at the age of 39? And while we’re on the subject, what’s wrong with mom jeans?

The midlife crisis, or at least the one depicted in popular media, has long been treated as more of a punchline than a genuine existential dilemma.

It’s the casual derision we reserve for people who dare to look beyond the limitations of their age bracket or the gentle self-mockery practised by people, like Lolo, who want to get in first with the ‘age-inappropriate’ gag.

The idea of a midlife crisis was first posed by a psychologist named Elliot Jacques when he presented his paper on ‘Death and the midlife crisis’ to the British Psychoanalytical Society in 1957.

The term was later popularised by writer Gail Sheehy, who developed upon Jacques’s ideas in her 1976 bestseller Passages: Predictable Crises of Adult Life. Sheehy framed the midlife crisis as a life stage that both men and women experience, but then, somewhere along the way, it became trivialised as a sort of male-centred second adolescence.

Suddenly, the midlife crisis was less about “the experience of one’s mortality”, as Jacques had put it, and more about fifty-something men indulging in sports cars, tight trousers and general self-gratification.

It’s really only in recent years that we’ve started to look at the midlife crisis through a different lens, firstly as a genuine period of reckoning and, secondly, as a transition that can affect women too — but in a very different way.

A new body of literature has brought the female midlife crisis and its unique challenges into sharp focus. There Will Be Lobster by Sara Arnell chronicles the writer’s “several-year period” of disruptive midlife shifts, anxiety and depression.

Why We Can’t Sleep by Ada Calhoun explores the new midlife crisis faced by Generation X. “Our lives can begin to feel like the latter seconds of a game of Tetris,” she writes, “where the descending pieces pile up faster and faster.”

For Pamela Druckerman, author of There Are No Grown-Ups, midlife is a time when women “can no longer wear anything ironically”; when “everyone you meet looks a little bit familiar” and when you are no longer the object of the male gaze.

Men still look at women in their 40s and 50s, writes Druckerman, but their gaze seems to say: “I would sleep with her, but only if doing so required no effort whatsoever.”

Midlife coach Alana Kirk (51) says the lack of direction can make the midlife period difficult to navigate.

“In our 20s and 30s, we followed very clear sign-posts: get an education, travel, build a career, find the person, buy the house… it’s all quite prescribed. And what you’re looking at now is 20 years with no clear sign-posts. This is your time to write the sign-posts, but that can be quite frightening.

“Women keep striving to achieve, and ticking boxes and the slump happens when that expectation meets reality. It’s like: ‘I’ve ticked all the boxes and, really, is this it? I wanted to feel more.’”

Midlife is different for women, she adds: “Men also have a lot of pressure, but they generally just want a bit more oomph in their life, whereas for women, it’s an absolutely fundamental change to the core of who you are. You stop being the breeder. You’ve probably birthed a family and this is the time when you start birthing yourself again.”

Alana experienced significant changes in her own life at the age of 45. “My marriage ended and my mum died. Within the space of 10 months, the family I came from and the family I created were both gone. Obviously, there was a lot of grief, but I went back to college in my late 40s and now I’m coaching.”

Her personal experience of midlife reinvention has made her wary of using the term ‘crisis’, she says. She prefers to think of midlife as an opportunity and in her work as a coach, she helps women explore the “enormous” possibilities that are available to them. “I think the word ‘crisis’ suggests a lack of control,” she adds.

The midlife years can also be a time when women with children begin to rethink the role of mother, says Dr Julie Rodgers of the Maynooth University Motherhood Project.

“For some women, this turning point in the motherhood trajectory is a moment when they get to claim back some of their own identity and that can be a really liberating period for women when they get to turn their attention to themselves,” she says.

“But it can also be very dark and that’s really society’s fault because we’re encouraged to give so much of ourselves and not really hone our individual identities and desires as mothers.

“When children leave, you end up with this sense of lack and loss and there’s not much discussion about how to negotiate that or how to get yourself back on track.

“You pour so much of yourself, in the way society wants you to, into motherhood and there’s not much of you left. Then you can be faced with this hole, like: ‘Who are you?’ You’ve lost potentially your sense of self and you don’t really know who you are and what you want anymore.”

The term ‘empty-nest syndrome’ is often used to describe the sense of loss parents experience when children fly the nest, but Julie says this catch-all term doesn’t quite convey the complexity of emotions that a mother may experience.

“We should never think of women just having this one singular reaction as we all react in different ways,” she says.

“For some women, it’s a moment of liberation, for some women, there can be a sense of loss and lack, and for some women, it can be a time of regret because they’ve been encouraged to pour so much of their identity into motherhood… They regret having been mothers and they think: ‘Why did I do this? I could have had a totally different life.’ And it’s still very taboo for mothers to express regret.”

The various challenges and reflections that converge during midlife are one matter, the hormonal shifts that usually occur simultaneously are quite another.

“The perimenopause and menopause adds on another layer of complexity and pressure,” says Loretta Dignam, founder of The Menopause Hub, who notes that the average age of perimenopause is 45, the average age of menopause is 51 and the average duration of symptoms is 7.4 years.

“It’s a long old time for a woman to be feeling this way and I think confidence and sense of self is one of the things that can get a bit of a beating,” she says.

“You could argue that it’s an opportunity for women to look at the third act, if you like, and say, ‘What do I want to do with the rest of my life?’, but actually, it’s very difficult if you’re caught up in this hormonal roller coaster to see the wood from the trees and a lot of women are just about hanging on.”

Loretta, who is now 58, says the menopause caught her both unprepared and uninformed. “My sleep was disturbed, I was getting up in the night to go to the loo, my libido was gone. I just described myself as a slow puncture… Most women think they’re too young for the menopause. I hit menopause at 50 and even I thought I was too young.

“In my research, 80pc of women are unprepared for menopause,” she adds. “They were just about able to cope before, but then things are appearing like anxiety, sleep disruption, brain fog, memory loss, lack of va-va-voom, irritability and mood changes.

“Women often report to us that they think they’re going mad. I was talking to a woman yesterday and she thought she was dying.”

The menopause represents a key difference between the way men and women might experience a midlife crisis, and while the idea of a male menopause, or ‘andropause’, has gained popularity in recent years, Loretta says it can’t be compared to the hormonal upheaval that women experience in their 40s and 50s.

“The jury is out on the andropause in the sense that a woman’s hormones fall off a cliff. It’s almost a straight line, whereas testosterone levels usually fall gradually.”

The decline of oestrogen during a woman’s menopause also triggers the decline of the ‘love hormone’ oxytocin, which kick-starts labour and influences maternal bonding, she explains. It’s a domino effect, with lower levels of oxytocin affecting the female impetus to nurture and care.

“[The decline of] oxytocin definitely has a big impact,” she says. “It becomes less about caring for everybody else and it’s now about caring for yourself. I saw it personally in my own life. Once my kids got to a certain age, it was like, okay, foot off the pedal now. And it feels like it’s a mental decision but, actually, it’s more than that.”

The menopause can be an emotionally turbulent time, but it’s worth noting that the transitional stages of a woman’s life don’t always dovetail neatly.

“We have this assumption that [menopause] means grown-up children, but a lot of women in midlife nowadays are raising really young children,” Julie says.

“So they’re having to negotiate perimenopause and menopause while they are mothers to five and six-year-olds. And when you think about that in terms of the drop in oxytocin, which we’re told is for maternal instinct, how do you negotiate that and be a mother to young children?”

Julie says the tendency to merge female identity with motherhood can also affect a woman’s perception of herself in midlife. “If society is aligning womanhood with the ability to procreate, then how does a woman negotiate the loss of that? There are feelings, I would imagine, of invisibility during menopause because of how highly we value reproduction.”

This brings us neatly to the subject of ‘invisible woman syndrome’, a social phenomenon said to affect women over 50 years old, as they grapple with age discrimination and a lack of representation in everything from film to fashion.

“In the fashion industry, I would say the older woman is 35-plus, which in any other realm of life would be ludicrous,” says fashion stylist Cathy O’Connor. “It’s all about marketing, ‘age is not sexy, age doesn’t sell’, yada, yada, yada.

“And then you take any television programme, any film, unless it is targeted to a certain audience, we’re just not there. And of course there is a feeling of invisibility because what reassures people ‘that people like us do things like this’, is that you’re seeing yourself reflected back, and that doesn’t happen in fashion.

“You’ve got brands whose customer base is older, but you will find they will put those clothes on models that are significantly younger because while they want to sell to the older woman, they don’t want to be affiliated with age. It’s like you’re the shameful friend… and then, at home, women have teenage daughters who are saying: ‘Mum, you’re not going out in that!’”

The messaging aimed at midlife women can lead to self-doubt and insecurity, says Cathy, especially when the “compare and despair” cycle of social media comes into the equation. “It can become a bit like: ‘I’ve given up on me, but look how beautifully dressed my children are.’”

Cathy, who is 61, doesn’t think of midlife as a crisis point, rather she sees it as an opportunity for reflection and reinvention. She believes that every stage of life is to be celebrated and her advice to women struggling with their midlife transition is to cultivate a sense of gravitate.

“I don’t mean that in some sort of Californian, meaningless way,” she says. “But when you look in the mirror, look at all that is great about you… the worst thing you can do is be invisible to yourself.”

Alana has a similarly glass-half-full outlook. She believes women have huge midlife potential, once they come out from the “overwhelm and the conditioning”, and her advice to women who are unsure of their next move is to “stop thinking about what you want your life to look like and start thinking about how you want your life to feel”.

“If you’re unlucky, this change happens to you,” she adds. “But if you’re lucky, you can grab this moment and the change happens within you, and for you.”

SUBSCRIBE FOR WEEKLY LIFE LESSONS

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, metus at rhoncus dapibus, habitasse vitae cubilia odio sed.

We hate SPAM. We will never sell your information, for any reason.